Pushing the needle: Turning points of a complex MSD program in Northeast Nigeria

Mid-August 2021, at our annual planning for Year 3, our Finance Team made a presentation on the program’s budget vs actual (BVA). Data from the presentation showed that after two years, the BVA was at 6% and the time elapsed was at 40%. Everyone agreed that results were invisible and in fact the donor had put the project on a three-month performance improvement plan. They called it an Activity Acceleration Plan - a name friendlier than the former. A budget to actual variance analysis is a process by which a company’s budget is compared to actual results and the reasons for the variance are interpreted. The purpose of a variance analysis is to provoke questions such as: why did one budget line perform better (or worse) than the others? Why are variances being caused? By execution failure? Changes in market conditions? An unexpected event or unrealistic forecast?

By the end of April 2022, exactly 8 months after, our Finance and Compliance Manager shared an analysis of the BVA again. The analysis output showed that our BVA stood at 57% on expenditure, 50% on time elapsed and 75%+ on scope. There were very minimal changes in the team - 95% of the team remained the same within this timeframe. “How is that possible?”, asked Tim Sparkman, a thought leader in systems thinking and co-founder of The Canopy Lab. Our story beats conventional wisdom. In fact, being a market systems development (MSD) professional, Tim was candid to ask the question that way. To others, it is simply unbelievable that a project can achieve the above in a short timescale with the same people.

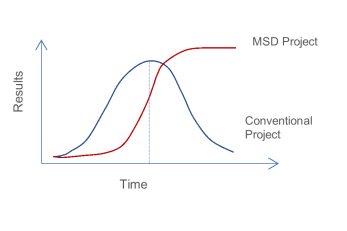

Before I explained what happened and how we account for our miraculous and astronomical achievement, let me revisit the foundations of MSD. It is not unusual for MSD programs to grossly underspend in their early years of implementation. In fact, several leaders in MSD have used a graph presented below to explain anticipated patterns of results and expenditures in comparison to conventional development projects/programs. Some of the BVA explanation could lie in the graph below.

Personally, my MSD journey with Tim dates more than a decade ago. Once, I was part of Tim’s team that delivered a very successful MSD program. I kept myself as his student in systems thinking for over a decade. Like the Feed the Future Nigeria Rural Resilience Activity, our earlier MSD project spent only 11% against 50% time elapsed. It could only spend 60% of the overall budget by the last year; and we had to seek a no cost extension and expand to new geographies. To this day, it is regarded as one of the most successful MSD projects. Back then, it was called M4P which means Markets for the Poor, or MMW4P meaning Making Markets Work for the Poor. The Making Markets Work for the Poor approach is a practical approach to development that increases the likelihood of achieving sustainable positive impact at scale. The approach acknowledges that people live in complex systems and thus provides frameworks to help break down complexity through a process of iterative analysis and strategic planning. The purpose is to go beyond initial symptoms of problems to identify underlying causes.

Speaking of results in M4P projects, “In the context of increasing pressure on development budgets, there has perhaps never been greater need for evidence that M4P ‘works’”, says Ben Fowler of MarketShares Associates. Like Tim, Ben is a well-respected personality within the MSD industry. I was also privileged to work with Ben on the same project for nearly two years. “A key tenet of the M4P approach is that it yields sustainable results at scale”, posits Ben, “however, these results often take time, as per the so-called ‘hockey stick’ curve of continuing sustainable impacts post-program”. Ben’s viewpoint is validating the graph above.

One of the founders of M4P/MSD Alan Gibson taught us that the approach focuses on creating lasting opportunities and benefits for poor people by tackling the underlying causes in the market system that block poor women, men, youth and other marginalized groups such as people who are living with disabilities, IDPs and refugees from improved market accessibility. The major difference between MSD and conventional economic support approaches is that solutions for these constraints are identified in the market. Hence, after a profound analysis of the root causes of the constraints, the private sector is assisted to define and provide a solution, through developing viable business models that benefit them and their clients. Our major role as development facilitators is to identify those business cases, then work with economic or political actors to bring about lasting changes in incentives, rules, etc. within markets, and ultimately improve the terms of participation for poor women and men.

Let me offer some hint to our BVA miracle. We are a resilience project in Nigeria. Our philosophy describes three types of resilience capacity: absorptive, adaptive and transformative capacity. These three capacities need to be enhanced to achieve resilient development outcomes, that is, the realization of rights and wellbeing in spite of shocks, stresses and uncertainty. Whereas we are fully an MSD project, we blend our approach with a resilience lens. We believe that the market system is a necessary condition for a meaningful resilience. Therefore, we also used targeted cash transfers to enhance the absorptive and adaptive capacities of individuals and market systems, helping individuals and markets to recover from the Covid-19 impacts. In fact, one third of our investments was in cash response.

So how did we achieve so much in a short timescale? What happened? Is it replicable in another similar setting? What were the nuances? Did luck hit us? First and foremost, the cash response intervention accounted for 60% of our BVA miracle. If one isolates it from the BVA computation, our graph would potentially be the same as other MSD projects. Below are some elements that I believe are replicable in other MSD projects although not fully, because our context played a very big role.

Workplan

We developed a workplan that would be implemented from Oct 1, 2021 to Sept 30, 2022. In our workplan, we designed 117 milestones and allotted quarterly targets for each milestone. We developed a Gantt Chart at the last pages of the workplan and followed our quarterly targets religiously. Those familiar with the MSD approach know that this practice is not alien to MSD. In our case, we were flexible on the “how” but were uncompromising on the “what”. At the start of the work planning processes, we agreed upon a 15-year vision to set the right direction, into the future and took a “shark-tank approach”.

Change of work flow

As of 1st Oct 2021, we reengineered our workflow. We established 27 interventions and used a determined and highly focused strategy in implementation. Each intervention was small enough to be managed by an individual across four states and yet large enough to attract private sector investments and create a meaningful impact. Northeast Nigeria is a very unique context. It meets all the characteristics of a thin market, yet if you compared to other thin markets, it does not qualify. Compared to other parts of Nigeria, it is so thin and so remote, yet compared to other countries its population is like twice the size of Rwanda. We are in four states but serving a market of almost 25million people, almost the size of Rwanda and Malawi combined and half the size of Tanzania, almost 83% size of Ghana and almost twice the size of Africa’s football giants, Senegal. With that population size, the chance of succeeding in promoting commercial activity is very high. In market sizing, the total number of potential buyers of a product or service within a given market, and the total revenue that these sales may generate are two important foundations.

Experimentation

Our history of underperformance turned us into daredevils when it comes to experimentation. But first, we democratized the workflow – every Intervention Manager, following his/her results chain, was able to develop a concept note to trial in the NEN marketplace, and we removed unnecessary layers of reviews. The team dared to experiment almost everything that was within their interventions. Experimentation came along with developing several partnerships. We needed partners to co-experiment with us. We sought after local private sector players because they have incentives and a stake in the local economy. Within a short timeframe, we mobilized 68 partners and everyone of our technical team found her/himself as a partner manager. We pushed ourselves so hard that one would literally feel out of place if a week was ending without tangible results to report. We pushed our partners hard too. Some partnerships had to drop because they could not move quickly at the market pace. We observed deadlines on a weekly, monthly and quarterly basis. Observing deadlines is a litmus test for discipline in our team. We dropped what wasn’t working and took to scale what was promising. We learnt quicker than we could remember to document.

Training and continuous self-improvement

In a short timescale, we accepted the fact that getting off the roller coaster of personal development was the best decision to make. After getting our team trained in the MSD approach, we knew that the training was good but not enough. It was good because the team was enthusiastic to learn MSD, but it was not enough because training could be treated as a one-off event. After formal training, we encouraged the team to improve by adopting a mindset of a 1% improvement. Research shows that consistency in improvement can build tremendous improvements, and over time can make a big difference to our success. It’s called the principle of ‘aggregate marginal gains’ and is the idea that if you improve by just 1% consistently, those small gains will add up to remarkable improvement. We see this everywhere in our lives. Big change and improvement can be and is achieved through small steps – but always with a grander vision and goal in mind. To reinforce this, we encouraged a reading culture and shipped in leadership books for virtually everyone in the team.

Culture of trust

The team felt trusted that they would deliver. We created a culture that tolerated failures but instilled discipline, reinforced a mindset of success, and a winning attitude. We swiftly changed how we managed ourselves and how we measured success. Mostly we align our measurement of success into business matrices such as financial performance and other improvements. We strive to be a partner that enables private sector players to succeed. We strive to assess what is working, analyze the business case and adapt with partners. We build our partnerships on mutual trust. We use a lean and flexible approach with minimal data and help firms analyze performance using their own business metrics such as value of sales, value of capital investments, number of individuals trading with our partners, number of people adopting new technologies and the overall number of individuals benefiting.

Focused on disciplined leadership

As management, we inspired leadership into the team. We used some leadership principles you find in Good to Great by Jim Collins. The book sheds light on virtually every area of management strategy and practice. We availed the book to several members of the team and asked people to read and practice the principles therein. We experimented with different types of leadership required to achieve greatness as evidenced by this book. We demanded a Culture of Discipline. We took Collins’ advice that when you combine a culture of discipline with an ethic of entrepreneurship, you get the magical alchemy of great results. Quoting Collins book, at one of the complex board meetings in November 2021, Sean Granville-Ross said “get the right people on the bus”. No doubt some people “had to off-board the bus”. Several times, I have told our team that it is nearly impossible to succeed without discipline. Some members of the team think this is my life slogan.

Pressed hard on productivity

We required of our team a productive work pattern. It is crucial to stay focused at work if you want to increase productivity. But it is easy to lose focus, as it is almost impossible to shut yourself to the external stimuli in the form of various distractions. How many times have you started to do a job, only to be distracted when something else comes up? It stops you from delivering results. For us, one of the distractions was endless online meetings. We cut that out almost completely. In the words of Mark Esper, Former United States Secretary of Defense, we told our team, “Stay focused on your mission, remain steadfast in your pursuit of excellence, and always do the right thing”.

Amplifying the Enterprise Investment Fund

Our project has a flexible limited fund for catalytic growth. We triggered it to mobilized growth-hungry private sector players, to invest into Northeast Nigeria. Like H. Bekkers and M. Zulfiqar posited, “The MSD approach is not exclusively characterized by interventions that are light-touch, involving short-duration technical assistance. More committed, medium-term and ‘heavier’ support is sometimes justified.” Our case considering that the cost of doing business justified heavier support. We are keen that our support package never violated core MSD principles. Some private-sector actors are making substantial investments at the firm and farm level in Northeast Nigeria. With these investments, significant productivity gains are being achieved relatively quickly among our participating firms and farmers. Slowly the transactions enabled by our catalytic funding are rolling back the high level of distrust between the various value chain actors. We are making “baby steps” in building relationships. We want to foster longer-term win-win relationships for the private sector rather than the prevailing one-off transactions. We are not yet there but it will happen.

Intervention Management Checklist

Our teams are scattered over four states, in five locations, and we totally rely on their discipline leadership for technical execution. Our intervention management checklist is something we developed for the project. It is a practical nine-step management tool for managing a complex project with diverse interventions spread over a large geography. Our results measurement team are custodians of the intervention checklist. The guys are ruthless when it comes to enforcing usage of the tool. They use it to support the implementation team to articulate their hypothesis clearly, and to systematically set and monitor targets which show whether events are occurring as expected. I invite complex programs to try out the use of the intervention management checklist. It worked for us.

The above are some and not all the reasons for our amplified achievement and performance. Looking ahead, are we there yet? Are we satisfied with our journey? How do we avoid the trap of complacency and settling in a safe zone?

Whereas we have achieved most of our output targets and we are on time and just above budget, to me the real work is just to start. Our Vision for Northeast Nigeria reads “the region achieves transformation in the economy driven by competitive, inclusive and resilient growth – where growth withstands the test of time, supported by structures and systems with the ability to adapt and evolve, overcome risks and challenges, and create new opportunities to maintain growth.” Joanna Ledgerwood would describe our approach as that which strives to create the foundation for lasting change where the market system – its functions and players – is equipped to meet future challenges and to continue to meet the changing needs of the poor. One whose result is sustained impact, rather than short-lived or dependent on further injections of aid. That is why we should forget the early wins in targets and the BVA analysis output for a moment. We have to keep a clear vision of how things would work better for large numbers of people in North East Nigeria without continued external intervention in future. Our next phase of work tactics is thus geared to facilitate and uphold long-term changes. Achieving output targets may merely create temporary shifts in incentives or behaviors. The changes we see today are not yet long term. That is why I say work is just starting.

Written by John Rachkara, Deputy Chief of Party, USAID funded Feed the Future Nigeria Rural Resilience Activity.

About the Feed the Future Nigeria Rural Resilience Activity

The Feed the Future Nigeria Rural Resilience Activity is a five-year, US$45 million program funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to facilitate economic recovery and growth in vulnerable, conflict-affected areas by promoting systemic change in market systems. The Activity is part of the U.S. Government's global hunger and food security initiative. It is aimed at empowering vulnerable households, communities and systems to cope with current shocks and stresses, and to be prepared to withstand future ones.

The Activity is implemented by Mercy Corps, in partnership with International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC) and Save the Children (SCI), primarily in the Northeast states of Adamawa, Borno, Gombe, and Yobe. Through the COVID-19 Mitigation Response Program, the Activity's operational areas also include Benue, Kebbi, Niger and Ebonyi states, as well as the Federal Capital Territory. Using market-led approaches, the Activity will move over 567,780 individuals out of chronic vulnerability and poverty.